She develops the batteries of the future – which will revolutionize the industry

NyTeknikThe researcher and entrepreneur Christina Lampe Önnerud is working on a new supercell architecture that will make the batteries of the future better, safer and cheaper.

2018-05-03 06:00

Ania Obminska

Cost, that’s my opinion, drives everything. If you can not find a cost-effective solution then you have nothing, “says Christina Lampe Önnerud. Photo: Jörgen Appelgren

“I have worked with Swedish innovators, engineers and companies throughout my career. At the moment, I’m partly here too, but I can not tell you so much more about it, “says Christina Lampe Önnerud when Ny Teknik meets her on a sunny day in April. Photo: Jörgen Appelgren

Cadenza Innovation has collaborated with Fiat, which tested Cadenza’s battery in a Fiat 500. Photo: Cadenza Innovation Photo: Cadenza Innovation

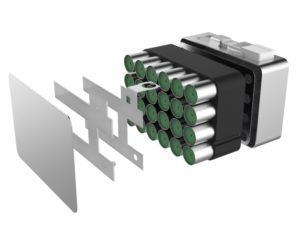

The researcher and entrepreneur Christina Lampe Önnerud is working on a new architecture for supercells. Photo: Cadenza Innovation

It has been thirteen years since Christina Lampe Önnerud, and Per started the company Boston-Power with the goal of creating more energy efficient batteries. Before they left the company in 2012 for a new management, they had succeeded in doing so.

With the new company Cadenza Innovation, the starting point is to reduce the cost of future batteries. When it becomes as cheap or cheaper to have an electric car compared to one who is on diesel or gasoline, yes there is a chance for a real breakthrough, Christina Lampe Önnerud thinks.

– Cost, it’s my opinion, drives everything. If you can not find a cost-effective solution then you have nothing, she says when Ny Teknik meets her with a sunny spring day in April.

She has lived in the United States for many years, but is in Sweden with her family to visit the family, she says first. Then she laughs and tells that there is another reason.

“In Sweden there is a strong tradition of engineering, innovation and then everything about sustainability, which makes me warm about the heart. I have worked with Swedish innovators, engineers and companies throughout my career. At the moment, I’m partly here for that reason, but I can not tell you so much more about it yet, she says.

Conversation with Swedish players about Cadenza’s batteries

But do you have a conversation here in Sweden with someone or a few because of your company’s work?

“Yes, definitely, about Cadenza’s technology and the supercell we are working on,” she says, without wishing to say more about which or what actors it is about.

Cadenza has developed a new method for building batteries in the form of supercells. Christina Lampe Önnerud says they have already taken known techniques and put them together to something that becomes much more effective than the options.

“Usually, it’s about taking a step back and wondering why does it look like this, why do we do this?

Christina Lampe Önnerud resembles her cell design at an egg carton. The “carton” is made of ceramic fiber mixed with a fire extinguishing material. It starts breaking first at 1000 degrees. The electrochemical energy rolls are the eggs, surrounded by a thin aluminum casing.

The anodes of each energy roll are connected to a copper conductor that transports current and emits heat. With the new architecture, the temperature should be even throughout the battery.

Each “egg carton” serves as a legobit, which can easily be built with another. The end result becomes more compact than existing solutions.

The battery has shredded components

Cadenza has removed what Christina Lampe Önnerud calls “a lot of unnecessary components”. The energy rolls, for example, share pressure equalization valves. Because the cell is larger, the cost and complexity of electronics for monitoring and control are also lowered.

“Tesla has had energy coins, where each roll is a separate battery, its own cell which has its own terminal, its own pressure valve and so on. In our case, I only need a terminal and a valve per legobit, “says Christina Lampe Önnerud.

If an energy roller would become overheated, or something else would occur in a cell, then the whole cell would disconnect itself. In a car with perhaps hundreds of cells, there should be no problem of disconnecting, as it’s only about 1 percent of the total energy. The driver receives a message about the error and when the car is left in stock, the error can either be corrected or the cell will be replaced. The old is recycled.

Cadenza’s technique is not dependent on any specific chemistry. On the cathode side you should be able to use, for example, nickel, cobalt or manganese. The legobit is adapted accordingly. This, says Christina Lampe Önnerud, is one of the things that makes the technology so powerful.

“If I can have a chemical flexibility, then I can also reduce the cost of the batteries. Nor do I depend on a special technique or special subcontractor. It provides a mobility that has not been in the industry earlier, she says.

Higher energy density at a lower cost

In lab tests, the new way of packing the energy coils should have given at least 30 percent higher energy density, measured in volume. It should also be a 30 percent cheaper solution.

The transport sector is not the only one that Cadenza Innovation is looking at. The company has chosen two focus areas where transport is the one. Power supply is the other.

Last year, Cadenza Innovation launched a collaboration with the state of New York. The purpose is to see if the new technology can contribute to a safer and more reliable energy supply in the densely populated city of New York. The next step is to test the technology in the demo scale. The hope of the company is to show that their model for storing energy in the “egg cartons” should be part of a future standard for the electricity grid.

“We think that a certain surface has been allocated that holds a box of batteries that have the same size all the time, but the efficiency of them can increase. Then you can get more and more energy as soon as the technology becomes available, in the same space.

Cadenza Innovation will not build any own factories. The idea is that Cadenza Innovation will help companies define what issues to solve, contribute excellence to ease the choice of battery chemistry, for example, and work close to the end-market. The actual customers will be the licensees who will build batteries based on the company’s cell design, both established factories and new ones.

Aiming to start mass production in the coming years

Later this year, it is expected to be clear which battery manufacturer will be the first to produce mass production according to Cadenza’s model. The idea is that this production will start by the end of 2019 or at the beginning of 2020. Conversations will be held with potential customers “in several places around the world,” says Christina Lampe Önnerud.

In Swedish Northvolt, she says it’s both exciting and fun to get a new player.

– Peter (Carlsson, CEO of Northvolt, reds.anm.) Has good experience from Tesla and has been dealing with some good people. It is still quite small and there is still a lot of work left, but of course it is super exciting. It’s fun to see a bet. There are quite a few things that must fall in place for it to work, but at the same time you have to start somewhere, says Christina Lampe Önnerud.

Christina Lampe Önnerud and Cadenza

Christina Lampe Önnerud was born 4 February 1967 in Ludvika. She has studied inorganic chemistry at Uppsala University, where she also studied lithium-ion batteries. Later she researched at MIT in Boston.

In 2005, she and her husband Per Önnerud founded the battery company Boston Power, which was sold to a Chinese company in 2012. That same year, the pair Önnerud started the company Cadenza Innovation, which has developed a new way of building batteries in the form of supercells.

Christina Lampe Önnerud has taken over 80 patents.

Last year, Cadenza Innovation entered into a long-term R & D agreement with Syrah Resources, which has the largest non-Chinese government agency. Together they will drive the development of graphite anodes to lithium ion batteries. Christina Lampe-Önnerud is also in the Syrah Resources Board.

“If we can do this right, we can help Syrah Resources to set up cost-effective production of anode materials, costs across the industry can go down. It would provide a very reliable subcontracting chain, “she says.

**** Translated from Swedish with Google Translate